How to approach search problems

with Querqy and searchHub

Limits of rule based query optimization

Some time ago, I wrote how searchHub boosts onsite search query parsing with Querqy. Now, with this blog post I want to go into much more detail by introducing new problems and how to address them. To this end, I will also consider the different rewriters that come with Querqy. However, I won’t cover details already well described in the Querqy documentation. Additionally, I will illustrate where our product searchHub fits into the picture and which tools are most suited for problem solving.

First: Understanding Term-Matching

In a nutshell the big challenge with site search, or the area of Information Retrieval more generally, is mapping user input to existing data.

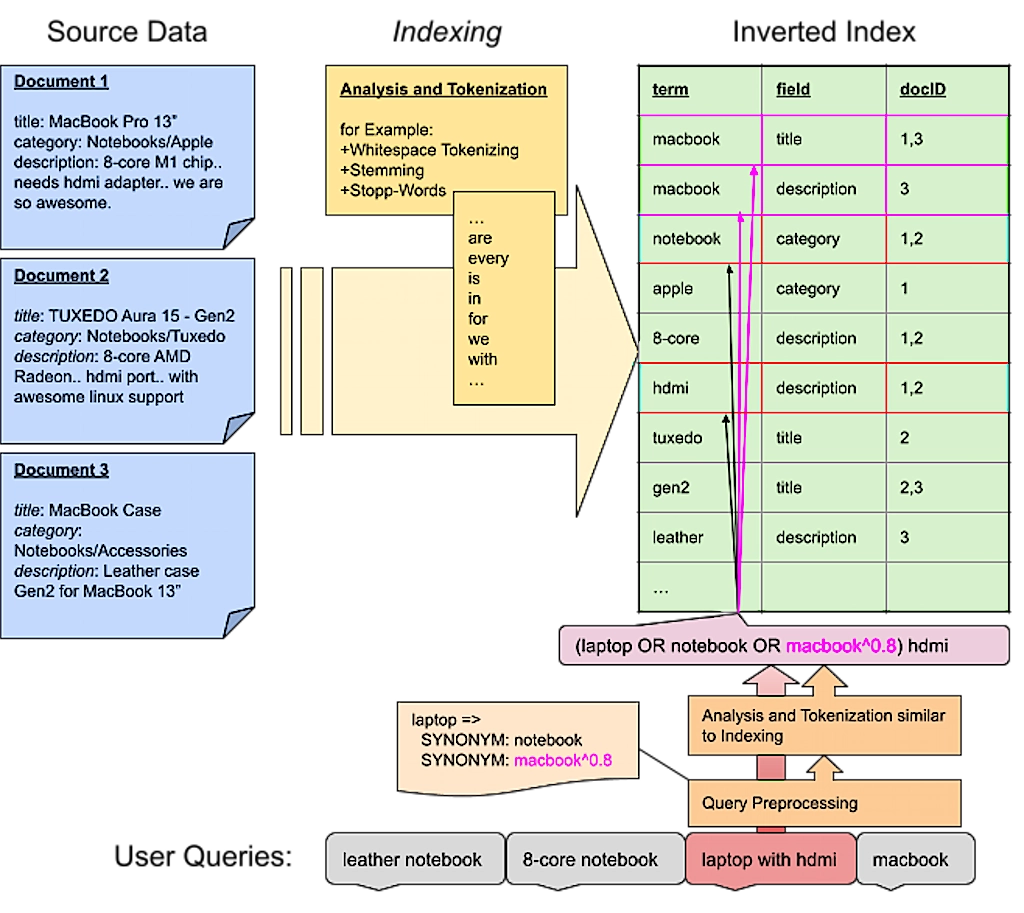

The most common approach is term matching. The basic idea is to split text into small, easy-to-manage pieces or “terms”. This process is called “tokenization”. Eventually these terms are transformed using “analyzers” and “filters”, in a process known as “analyzing”. Finally, this process is applied to the source data during “indexing” and the results are stored in an “inverted index”. This index stores the relationship of the newly produced terms to the fields and the documents they appear in.

This same processing is done for every incoming user query. Newly produced terms are looked up in an inverted index and the corresponding document ids become the queries’ result set. Of course this is a simplified picture, but it helps to understand the basic idea. Under the hood, considerably more effort is necessary in order to support partial matches, get proper relevance calculation etc.

Be aware that, in addition to everything described above, rules too must be applied during query preprocessing. The following visualization illustrates the relationship and impact of synonyms on query matching.

Term matching is also the approach of Lucene – the core used inside Elasticsearch and Solr. On that note: most search-engines work this way, though many new approaches are gaining acceptance across the market.

A Rough Outline of Site Search Problems

Term matching seems rather trivial if the terms match exactly: The user searches for “notebook” and gets all products that contain the term “notebook”. If you’re lucky, all these products are relevant for the user.

However, in most cases, the user – or rather we, as the ones who built search and are interested in providing excellent user experiences – is not so lucky. Let’s classify some problems that arise with that approach and how to fix them.

What is Term Mismatch?

In my opinion, this is the most common problem: One or more terms the user entered aren’t used in the data. For example the user searches for “laptop” but the relevant products within the data are titled “notebook”.

This is solved easily by creating a “synonym” rewrite rule. This is how that rule looks in Querqy:

laptop =>

SYNONYM: notebook

With that rule in place, each search for “laptop” will also search for “notebook”. Additionally, a search for “laptop case” is handled accordingly so the search will also find “notebook case”. You can also apply a weight to your synonym. This is useful when other terms are also found and you want to rank them lower:

laptop =>

SYNONYM: notebook

SYNONYM: macbook^0.8

Another special case of term mismatching are numeric attributes: users search for ‘13 inch notebook’ but some of the relevant products, for example, might have the attribute set to a value of ‘13.5’. Querqy helps with rules that make it easy to apply filter ranges and even normalize numeric attributes. For example, by recalculating inches into centimeters, in case there are product attributes that are searched in both units. Check out the documentation of the “Number Unit Rewriter” for detailed and good examples.

However there are several cases where such rules won’t fix the problem:

- In the event the user makes a typo: the rule no longer matches.

- In the event the user searches for the plural spelling “notebooks”: the rule no longer applies, unless an additional stemming filter is used prior to matching.

- The terms might match irrelevant products, like accessories or even other products using those same terms (e.g. the “paper notebook” or “macbook case”)

With searchHub preprocessing, we ensure user input is corrected before applying Querqy matching rules. At least this way the first two problems are mitigated.

How to Deal with Non-Specific Product Data?

The “term mismatch problem” is worse, if the products have no explicit name. Assume all notebooks are classified only by their brand and model names. For example: “Surface Go 12”, and put together with accessories and other product-types into a “computers & notebooks” category.

First of all some analysis needs to stem the plural term “notebooks” to “notebook” in the data and also in potential queries. This is something your search engine has to support. An alternative approach is to just search fuzzily through all the data, making it easier to match such minor differences. However, this may lead to other problems, for example not all stems have a low edit distance (e.g. cacti/cactus). Or yet another issue: other similar but unrelated words might match (shirts/shorts). More about that below, when I talk about typos.

Nevertheless, a considerable amount of irrelevant products will still match. Even ranking can’t help you here. You see, with ranking you’re not just concerned with relevance, but mostly looking for the greatest possible impact of your business rules. The only solution within Querqy is to add granular filters for that specific query:

"notebook" =>

SYNONYM: macbook^0.9

SYNONYM: surface^0.8

FILTER: * price:[400 TO 3000]

FILTER: * -title:pc

A little explanation:

- First of all this “rule set” only applies to the exact query “notebook”. That’s what the quotes signify.

- The synonym rules also include matches for “macbook” and “surface” in descending order.

- Then we use filters to ensure only mid to high price products are shown excluding those with “pc” in the title field.

Noticeably, such rules get really complicated. Oftentimes there are products that can’t be matched at all. And what’s more: rules only fix the search for a specific query. Even if searchHub could handle all the typos etc. a shop with such bad data quality will never escape manual rule hell.

This makes the solution obvious: fix your data quality! Categories and product names are the most important data for term-matching search:

- Categories should not contain combinations of words. Or if they do, don’t use such categories for searching. Also at least the final category level should name the “things” it contains (use “Microsoft Notebooks” instead of a category hierarchy “Notebook” > “Microsoft”) Also be as specific as possible (use “computer accessories” instead of “accessories”, or even “mice” and “keyboards”).

- Similar for product names: they should contain the most specific product type possible and attributes that only matter for that product.

searchHub’s analysis tool “SearchInsights” helps by analyzing which terms are searched most often and which attributes are relevant for associated product types.

How to Deal with Typos

The problem is obvious: User queries with typos need a more tenable solution. Correcting them all with rules would actually be insane. However, handling prominent typos or “alternative spellings” using Querqy’s “Replace Rewriter” still might make sense. Querqy has a minimalistic syntax easily allowing the configuration of lots of rules. It also allows substring correction using a simple wildcard syntax.

Example rule file:

leggins; legins; legings => leggings

tshirt; t shirt => t-shirt

Luckily, all search engines support some sort of fuzzy matching as well. Most of them use a variation of the “Edit Distance” algorithm that accepts a match of another term if only one or two characters differ. Nevertheless fuzzy matching is also mismatch prone. Even more so if used for every incoming term. For example, depending on the algorithm used, “shirts” and “shorts” have a low edit distance to each other but mean different things.

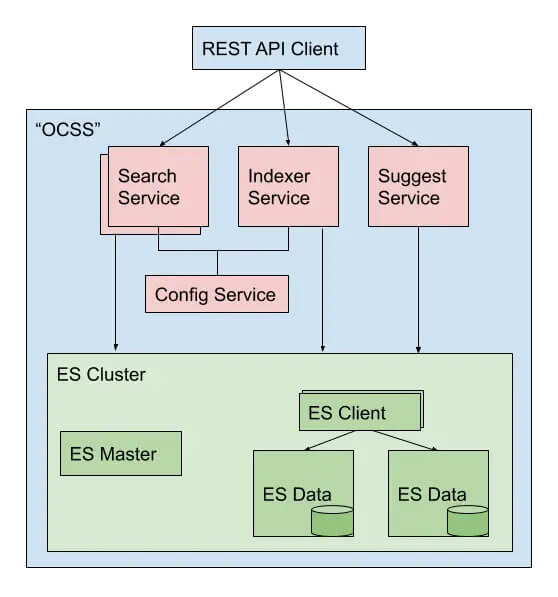

For this reason Elasticsearch offers the option to limit the maximum edit distance based on query length. This means, no fuzzy search will be initiated for short terms due to their propensity for fuzzy mismatches. Our project OCSS (Open Commerce Search Stack) moves fuzzy search to a later stage during query relaxation. This means we first try exact and stemmed terms, and only if there are no matches do we use fuzzy search. Also running spell-correction in parallel fixes typos in single words of a multi-term query. (some details are described in this post)

With searchHub we use extensive algorithms to achieve greater precision for potential misspellings. We calculate them once, then store the results for significantly faster real-time correction.

Unfortunately, if there are typos in the product data the problem gets awkward. In these cases, the correctly spelled queries won’t find potentially relevant products. Even if such typos can consistently be fixed, the hardest part is detecting which products weren’t found. Feel free to contact us if you need help with this!

Cross-field Matches

Best case scenario: users search for “things”. These are terms that name the searched items, for example “backpack” instead of “outdoor supplies”. Such specific terms are mostly found in the product title. If the data is formatted well, most queries can be matched to the product’s titles. But if the user searches more generic terms or adds more context to the query, things might get difficult.

Normally, a search index is set up to search in all available data fields, e.g. titles, categories, attributes and even long descriptions – which often have quite noisy data. Of course matches in those fields must be scored differently, nevertheless it happens that terms do get matched in the descriptions of irrelevant products. For example, the term “dress” can be part of many description texts for accessory products, that describe how good they might be combined with your next “dress”.

With Querqy you can set up rules for single terms and restrict them to a certain data field. That way you can avoid such matches:

Example rule file:

dress =>

FILTER: * title:dress

But you should also be careful with such rules, since they would also match for multi-term queries like “shoes for my dress”. Here query understanding is key to mapping queries to the proper data terms. More about this below under “Terms in Context”.

Decomposition

This problem arises mostly for several European languages, like Dutch, Swedish, Norwegian, German etc. where words can be combined for new, mostly more specific words. For example the German word “federkernmatratze” (box spring mattress) is a composite of the words “feder” (spring), “kern” (core/inner) and “matratze” (mattress).

First problem with compound words: There are no specific rules about how words can be combined and what that means for semantics, only that the last word in a series determines the “subject” classification. Is a compound word made of many words, then each word in the series needs to be placed before the “subject” which always has to appear at the end.

The following German example makes this clear: “rinderschnitzel” is a “schnitzel” made of beef (Rinder=Beef – meaning that it’s a beef schnitzel) but a “putenschnitzel” is a schnitzel made of turkey (puten=turkeys). Here the semantics come from the implicit context. And you can even say “rinderputenschnitzel” meaning a turkey schnitzel with beef. But you wouldn’t say “putenrinderschnitzel” because the partial compound word “putenrinder” would mean “beef of a turkey” – no one says that. 🙂

By the way, that concept or even some of those words have swapped over into English. For example: “kindergarden” or “basketball”, however in German, for many generic compound words, it’s possible to also use the words separately: “Damenkleid” (women’s dress) can also be named “Kleid für Damen” (dress for women).

The impending problem with these types of words is bidirectional though: these cases exist both inside the data, and come from users searching for them. Let’s distinguish between the two cases:

The Problem When Users Enter Compound Words

The problem occurs when the user searches for the compound word but the relevant products contain the single words. In English that doesn’t make sense (e.g. no product title would have “basket-ball” written separately. In German however the query “damenschuhe” (women’s shoes) must also match “schuhe” (“shoes”) in the category “damen” (“women”) or “schuhe für damen” (shoes for women).

Querqy’s “Word Break Rewriter” is good for such cases. It uses your indexed data as a dictionary to split up compound words. You can even control it by defining a specific data field as a dictionary. This can either be a field with known precise and good data or a field that you artificially fill with proper data.

In the slightly different case where the user searches for the decompounded version (“comfort mattress”) and the data contains the compound word (“comfortmattress”) Querqy helps with the “Shingle Rewriter”. It simply takes adjacent words and combines the terms. These are called “shingles”. It’s then possible to match them optionally in the data as well. A query could look like this:

![]()

If decompounding with tools like Wordbreak fails, you’re left with only one option: rewrite such queries. For this use case Querqy’s “Replace Rewriter” was developed. However, because searchHub picks the spelling with the better KPIs: like queries with low exitRates or high clickRates, we solve such problems automatically.

Dealing with Compound Words within the Data

Assume “basketball” is the term of the indexed products. Now if a user searches for “ball” he would most likely see the basketball inside the result as well. In this case the decomposition has to take place during indexing in order to have the term “ball” indexed for all the basketball products. This is where neither Querqy nor searchHub can help you (yet). Instead you have to use a decompounder during indexing and make sure to index all decompounded terms with those documents as well.

In both cases however, typos and partial singular/plural words might lead to undesirable results. This is handled automatically with searchHub’s query analysis.

How to Handle Significant Semantic Terms

Terms like “cheap”, “small”, and “bright” most likely won’t match any useful product related terms inside the data. Of course they also have different meanings depending on their context. A “small notebook” means a display size of 10 to 13 inches, while a small shirt means size S.

With Querqy you can specify rules that apply filters depending on the context of such semantic terms.

small notebook =>

FILTER: * screen_size:[10 TO 14]

small shirt =>

FILTER: * size:S

But as you might guess, such rules easily become unmanageable due to thousands of edge cases. As a result, you’ll most likely only run these kinds of rules for your top queries.

Solutions like Semknox try to solve this problem by using a highly complex ontology that understands query context and builds such filters or sortings automatically based on attributes that are indexed within your data.

With searchHub we recommend redirecting users to curated search result pages, where you filter on the relevant facets and even change the sorting. For example: order by price if someone searches for “cheap notebook”.

Terms in Context

A lot of terms have different meanings depending on their context. Like a notebook could be an electronic device or a paper device to take notes. A similar case for the word “mobile”: on its own the user is most likely searching for a smartphone. But in the context of the words “disk”, “notebook” or “home” , completely different things are meant.

Also brands tend to use common words for special products, like the label “orange” from “Hugo Boss”. In a fashion store this might become problematic if someone actually searches for the color “orange” in combination with other terms.

Next, broad queries like “dress” need more context to get more fitting results. For example a search for “standard women’s dresses” should not deliver the same types of results as a search for “dress suit”.

There is no specific problem about it and thus also no specific way to solve it. Just keep it in mind when writing rules. With Querqy you can use quotes on the input query to restrict it to be only for term beginnings, endings or full query matches.

With quotes around the input, the rule only matches the exact query ‘dress’:

"dress" =>

FILTER: * title:dress

With a quote at the beginning of the input, the rule only matches queries starting with ‘dress’:

"dress =>

FILTER: * title:dress

With a quote at the end of the input, the rule only matches queries ending with ‘dress’:

dress" =>

FILTER: * title:dress

Of course this may lead to even more rules, as you strive for more precision to ensure you’re not muddying or restricting your result set. But there’s really no way to prevent it, we’ve seen it in almost every project we’ve been involved: sooner or later the rules get out of control. At some point, there are so many queries with bad results that it makes more sense to delete rules rather than add new ones. The best option is to start fixing the underlying data to avoid “workaround rules” as much as possible.

Conclusion

At first glance, term matching is easy. But language is difficult. And this post merely scratches the surface of it. Querqy, with all the different rule possibilities, helps you handle special cases. searchHub locates the most important issues with “SearchInsights”. It also helps reduce the amount of rules and increase the impact of the few rules you do build.