This article continues the work on our analytics application from Part 1. You will need to read Part 1 to understand the content of this post. “How To DIY Site search analytics — Part 2” will add the following features to our application:

How-To Site-Search Analytics follow these steps

- Upload CSV files containing our E-Commerce KPIs in a way easily readable by humans.

- Convert the CSV files into Apache Parquet format for optimal storage and query performance.

- Upload Parquet files to AWS S3, optimized for partitioned data in Athena.

- Make Athena aware of newly uploaded data.

CSV upload to begin your DIY for Site Search Analytics

First, create a new Spring-Service that manages all file operations. Open your favorite IDE where you previously imported the application in part 1 and create a new class called FileService in the package com.example.searchinsightsdemo.service and paste in the following code:

@Service

public class FileService {

private final Path uploadLocation;

public FileService(ApplicationProperties properties) {

this.uploadLocation = Paths.get(properties.getStorageConfiguration().getUploadDir());

}

public Path store(MultipartFile file) {

String filename = StringUtils.cleanPath(file.getOriginalFilename());

try {

if (file.isEmpty()) {

throw new StorageException("Failed to store empty file " + filename);

}

if (filename.contains("..")) {

// This is a security check, should practically not happen as

// cleanPath is handling that ...

throw new StorageException("Cannot store file with relative path outside current directory " + filename);

}

try (InputStream inputStream = file.getInputStream()) {

Path filePath = this.uploadLocation.resolve(filename);

Files.copy(inputStream, filePath, StandardCopyOption.REPLACE_EXISTING);

return filePath;

}

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new StorageException("Failed to store file " + filename, e);

}

}

public Resource loadAsResource(String filename) {

try {

Path file = load(filename);

Resource resource = new UrlResource(file.toUri());

if (resource.exists() || resource.isReadable()) {

return resource;

}

else {

throw new StorageFileNotFoundException("Could not read file: " + filename);

}

}

catch (MalformedURLException e) {

throw new StorageFileNotFoundException("Could not read file: " + filename, e);

}

}

public Path load(String filename) {

return uploadLocation.resolve(filename);

}

public Stream<Path> loadAll() {

try {

return Files.walk(this.uploadLocation, 1)

.filter(path -> !path.equals(this.uploadLocation))

.map(this.uploadLocation::relativize);

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new StorageException("Failed to read stored files", e);

}

}

public void init() {

try {

Files.createDirectories(uploadLocation);

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new StorageException("Could not initialize storage", e);

}

}

That’s quite a lot of code. Let’s summarize the purpose of each relevant method and how it helps To DIY Site Search Analytics:

- store: Accepts a MultipartFile passed by a Spring Controller and stores the file content on disk. Always pay extra attention to security vulnerabilities when dealing with file uploads. In this example, we use Spring’s StringUtils.cleanPath to guard against relative paths, to prevent someone from navigating up our file system. In a real-world scenario, this would not be enough. You’ll want to add more checks for proper file extensions and the like.

- loadAsResource: Returns the content of a previously uploaded file as a Spring Resource.

- loadAll: Returns the names of all previously uploaded files.

To not unnecessarily inflate the article, I will refrain from detailing either the configuration of the upload directory or the custom exceptions. As a result, please review the packages com.example.searchinsightsdemo.config, com.example.searchinsightsdemo.service and the small change necessary in the class SearchInsightsDemoApplication to ensure proper setup.

Now, let’s have a look at the Spring Controller. Using the newly created service, create a Class FileController in the package com.example.searchinsightsdemo.rest and paste in the following code:

@RestController

@RequestMapping("/csv")

public class FileController {

private final FileService fileService;

public FileController(FileService fileService) {

this.fileService = fileService;

}

@PostMapping("/upload")

public ResponseEntity<String> upload(@RequestParam("file") MultipartFile file) throws Exception {

Path path = fileService.store(file);

return ResponseEntity.ok(MvcUriComponentsBuilder.fromMethodName(FileController.class, "serveFile", path.getFileName().toString()).build().toString());

}

@GetMapping("/uploads")

public ResponseEntity<List<String>> listUploadedFiles() throws IOException {

return ResponseEntity

.ok(fileService.loadAll()

.map(path -> MvcUriComponentsBuilder.fromMethodName(FileController.class, "serveFile", path.getFileName().toString()).build().toString())

.collect(Collectors.toList()));

}

@GetMapping("/uploads/{filename:.+}")

@ResponseBody

public ResponseEntity<Resource> serveFile(@PathVariable String filename) {

Resource file = fileService.loadAsResource(filename);

return ResponseEntity.ok()

.header(HttpHeaders.CONTENT_DISPOSITION, "attachment; filename="" + file.getFilename() + """).body(file);

}

@ExceptionHandler(StorageFileNotFoundException.class)

public ResponseEntity<?> handleStorageFileNotFound(StorageFileNotFoundException exc) {

return ResponseEntity.notFound().build();

}

}

Nothing special. We just provided request mappings to;

- Upload a file

- List all uploaded files

- Serve the content of a file

This will ensure the appropriate use of the service methods. Time to test the new functionality, start the Spring Boot application and run the following commands against it:

# Upload a file:

curl -s http://localhost:8080/csv/upload -F file=@/path_to_sample_application/sample_data.csv

# List all uploaded files

curl -s http://localhost:8080/csv/uploads

# Serve the content of a file

curl -s http://localhost:8080/csv/uploads/sample_data.csv

The sampledata.csv file can be found within the project directory. However, you can also use any other file.

Convert uploaded CSV files into Apache Parquet

We will add another endpoint to our application which expects the name of a previously uploaded file that should be converted to Parquet. Please note that AWS also offers services to accomplish this; however, I want to show you how to DIY.

Go to the FileController and add the following method:

@PatchMapping("/convert/{filename:.+}")

@ResponseBody

public ResponseEntity<String> csvToParquet(@PathVariable String filename) {

Path path = fileService.csvToParquet(filename);

return ResponseEntity.ok(MvcUriComponentsBuilder.fromMethodName(FileController.class, "serveFile", path.getFileName().toString()).build().toString());

}

As you might have already spotted, the code refers to a method that does not exist on the FileService. Before adding that logic though, we first need to add some new dependencies to our pom.xml which enable us to create Parquet files and read CSV files:

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.parquet</groupId>

<artifactId>parquet-hadoop</artifactId>

<version>1.12.0</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.hadoop</groupId>

<artifactId>hadoop-common</artifactId>

<version>3.3.0</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.hadoop</groupId>

<artifactId>hadoop-core</artifactId>

<version>1.2.1</version>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.apache.commons</groupId>

<artifactId>commons-csv</artifactId>

<version>1.8</version>

</dependency>

After updating the maven dependencies, we are ready to implement the missing part(s) of the FileService:

public Path csvToParquet(String filename) {

Resource csvResource = loadAsResource(filename);

String outputName = getFilenameWithDiffExt(csvResource, ".parquet");

String rawSchema = getSchema(csvResource);

Path outputParquetFile = uploadLocation.resolve(outputName);

if (Files.exists(outputParquetFile)) {

throw new StorageException("Output file " + outputName + " already exists");

}

org.apache.hadoop.fs.Path path = new org.apache.hadoop.fs.Path(outputParquetFile.toUri());

MessageType schema = MessageTypeParser.parseMessageType(rawSchema);

try (

CSVParser csvParser = CSVFormat.DEFAULT

.withFirstRecordAsHeader()

.parse(new InputStreamReader(csvResource.getInputStream()));

CsvParquetWriter writer = new CsvParquetWriter(path, schema, false);

) {

for (CSVRecord record : csvParser) {

List<String> values = new ArrayList<String>();

Iterator<String> iterator = record.iterator();

while (iterator.hasNext()) {

values.add(iterator.next());

}

writer.write(values);

}

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new StorageFileNotFoundException("Could not read file: " + filename);

}

return outputParquetFile;

}

private String getFilenameWithDiffExt(Resource csvResource, String ext) {

String outputName = csvResource.getFilename()

.substring(0, csvResource.getFilename().length() - ".csv".length()) + ext;

return outputName;

}

private String getSchema(Resource csvResource) {

try {

String fileName = getFilenameWithDiffExt(csvResource, ".schema");

File csvFile = csvResource.getFile();

File schemaFile = new File(csvFile.getParentFile(), fileName);

return Files.readString(schemaFile.toPath());

}

catch (IOException e) {

throw new StorageFileNotFoundException("Schema file does not exist for the given csv file, did you forget to upload it?", e);

}

}

That’s again quite a lot of code, and we want to relate it back to How best To DIY Site Search Analytics. So let’s try to understand what’s going on. First, we load the previously uploaded CSV file Resource that we want to convert into Parquet. From the resource name, we derive the name of an Apache Parquet schema file that describes the data types of each column of the CSV file. This results from Parquet’s binary file structure, which allows encoded data types. Based on the definition we provide in the schema file, the code will format the data accordingly before writing it to the Parquet file. More information can be found in the official documentation.

The schema file of the sample data can be found in the projects root directory:

message m {

required binary query;

required INT64 searches;

required INT64 clicks;

required INT64 transactions;

}

It contains only two data types:

- binary: Used to store the query — maps to String

- INT64: Used to store the KPIs of the query — maps to Integer

The content of the schema file is read into a String from which we can create a MessageType object that our custom CsvParquetWriter, which we will create shortly, needs to write the actual file. The rest of the code is standard CSV parsing using Apache Commons CSV, followed by passing the values of each record to our Parquet writer.

It’s time to add the last missing pieces before we can create our first Parquet file. Create a new class CsvParquetWriter in the package com.example.searchinsightsdemo.parquet and paste in the following code:

...

import org.apache.hadoop.fs.Path;

import org.apache.parquet.hadoop.ParquetWriter;

import org.apache.parquet.hadoop.metadata.CompressionCodecName;

import org.apache.parquet.schema.MessageType;

public class CsvParquetWriter extends ParquetWriter<List<String>> {

public CsvParquetWriter(Path file, MessageType schema) throws IOException {

this(file, schema, DEFAULT_IS_DICTIONARY_ENABLED);

}

public CsvParquetWriter(Path file, MessageType schema, boolean enableDictionary) throws IOException {

this(file, schema, CompressionCodecName.SNAPPY, enableDictionary);

}

public CsvParquetWriter(Path file, MessageType schema, CompressionCodecName codecName, boolean enableDictionary) throws IOException {

super(file, new CsvWriteSupport(schema), codecName, DEFAULT_BLOCK_SIZE, DEFAULT_PAGE_SIZE, enableDictionary, DEFAULT_IS_VALIDATING_ENABLED);

}

}

Our custom writer extends the ParquetWriter class, which we pulled in with the new maven dependencies. I added some imports to the snippet to visualize it. The custom writer does not need to do much; just call some super constructor classes with mostly default values, except that we use the SNAPPY codec to compress our files for optimal storage and cost reduction on AWS. What’s noticeable, however, is the CsvWriteSupport class that we also need to create ourselves. Create a class CsvWriteSupport in the package com.example.searchinsightsdemo.parquet with the following content:

...

import org.apache.hadoop.conf.Configuration;

import org.apache.parquet.column.ColumnDescriptor;

import org.apache.parquet.hadoop.api.WriteSupport;

import org.apache.parquet.io.ParquetEncodingException;

import org.apache.parquet.io.api.Binary;

import org.apache.parquet.io.api.RecordConsumer;

import org.apache.parquet.schema.MessageType;

public class CsvWriteSupport extends WriteSupport<List<String>> {

MessageType schema;

RecordConsumer recordConsumer;

List<ColumnDescriptor> cols;

// TODO: support specifying encodings and compression

public CsvWriteSupport(MessageType schema) {

this.schema = schema;

this.cols = schema.getColumns();

}

@Override

public WriteContext init(Configuration config) {

return new WriteContext(schema, new HashMap<String, String>());

}

@Override

public void prepareForWrite(RecordConsumer r) {

recordConsumer = r;

}

@Override

public void write(List<String> values) {

if (values.size() != cols.size()) {

throw new ParquetEncodingException("Invalid input data. Expecting " +

cols.size() + " columns. Input had " + values.size() + " columns (" + cols + ") : " + values);

}

recordConsumer.startMessage();

for (int i = 0; i < cols.size(); ++i) {

String val = values.get(i);

if (val.length() > 0) {

recordConsumer.startField(cols.get(i).getPath()[0], i);

switch (cols.get(i).getType()) {

case INT64:

recordConsumer.addInteger(Integer.parseInt(val));

break;

case BINARY:

recordConsumer.addBinary(stringToBinary(val));

break;

default:

throw new ParquetEncodingException(

"Unsupported column type: " + cols.get(i).getType());

}

recordConsumer.endField(cols.get(i).getPath()[0], i);

}

}

recordConsumer.endMessage();

}

private Binary stringToBinary(Object value) {

return Binary.fromString(value.toString());

}

}

Here we extend WriteSupport where we need to override some more methods. The interesting part is the write method, where we need to convert the String values, read from our CSV parser, into the proper data types defined in our schema file. Please note that you may need to extend the switch statement should you require more data types than in the example schema file.

Turning on the Box

Testing time, start the application and run the following commands:

# Upload the schema file of the example data

curl -s http://localhost:8080/csv/upload -F file=@/path_to_sample_application/sample_data.schema

# Convert the CSV file to Parquet

curl -s -XPATCH http://localhost:8080/csv/convert/sample_data.csv

If everything worked correctly, you should find the converted file in the upload directory:

[user@user search-insights-demo (⎈ |QA:ui)]$ ll /tmp/upload/

insgesamt 16K

drwxr-xr-x 2 user user 120 4. Mai 10:34 .

drwxrwxrwt 58 root root 1,8K 4. Mai 10:34 ..

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 114 3. Mai 15:44 sample_data.csv

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 902 4. Mai 10:34 sample_data.parquet

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 16 4. Mai 10:34 .sample_data.parquet.crc

-rw-r--r-- 1 user user 134 4. Mai 10:31 sample_data.schema

You might be wondering why the .parquet file size is greater than the .csv file. As I said, we are optimizing the storage size as well. The answer is pretty simple. Our CSV file contains very little data, and since Parquet stores the data types and additional metadata in the binary file, we don’t gain the benefit of compression. However, your CSV file will have more data, so things will look different. The raw CSV data of a single day from a real-world scenario is 11.9 MB whereas the converted Parquet file only weights 1.4 MB! That’s a reduction of 88% which is pretty impressive.

Upload the Parquet files to S3

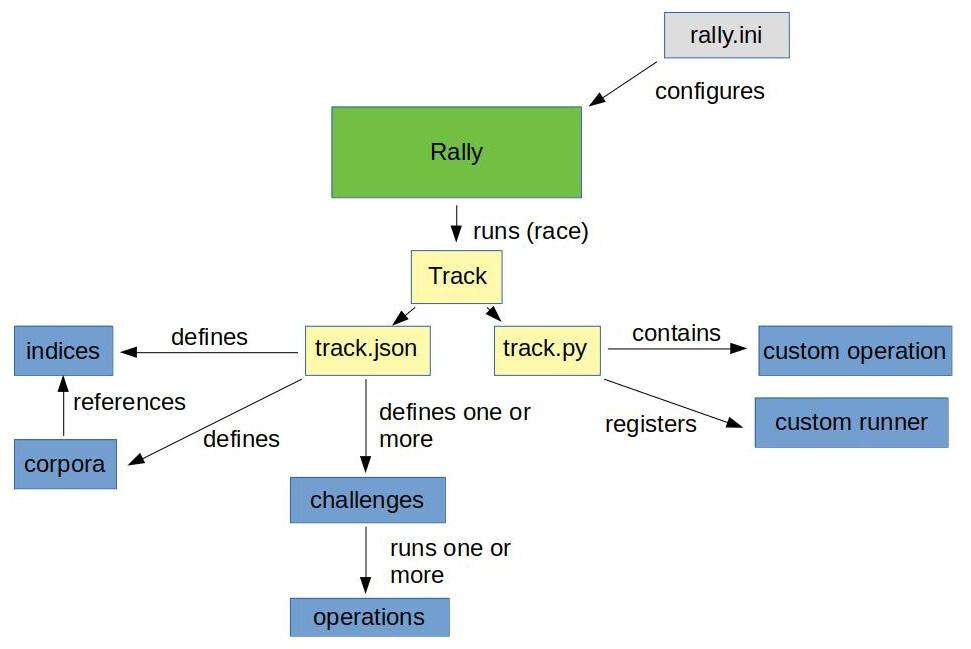

Now that we have the parquet files locally, it’s time to upload them to AWS S3. We already created our Athena database, in part one, where we enabled partitioning by a key called dt:

...

PARTITIONED BY (dt string)

STORED AS PARQUET

LOCATION 's3://search-insights-demo/'

this means we need to upload the files into the following bucket structure:

├── search-insights-demo

│ └── dt=2021-05-04/

│ └── analytics.parquet

Each parquet file needs to be placed in a bucket with the prefix dt= followed by the date relative to the corresponding KPIs. The name of the parquet file does not matter as long as its extension is .parquet.

It’s Hack Time

So let’s start coding. Add the following method to the FileController:

@PatchMapping("/s3/{filename:.+}")

@ResponseBody

public URL uploadToS3(@PathVariable String filename) {

return fileService.uploadToS3(filename);

}

and to the FileService respectively:

public URL uploadToS3(String filename) {

Resource parquetFile = loadAsResource(filename);

if (!parquetFile.getFilename().endsWith(".parquet")) {

throw new StorageException("You must upload parquet files to S3!");

}

try {

AmazonS3 s3 = AmazonS3ClientBuilder.standard().build();

File file = parquetFile.getFile();

long lastModified = file.lastModified();

LocalDate partitionDate = Instant.ofEpochMilli(lastModified)

.atZone(ZoneId.systemDefault())

.toLocalDate();

String bucket = String.format("search-insights-demo/dt=%s", partitionDate.toString());

s3.putObject(bucket, "analytics.parquet", file);

return s3.getUrl(bucket, "analytics.parquet");

}

catch (SdkClientException | IOException e) {

throw new StorageException("Failed to upload file to s3", e);

}

}

The code won’t compile before adding another dependency to our pom.xml:

<dependency>

<groupId>com.amazonaws</groupId>

<artifactId>aws-java-sdk-s3</artifactId>

<version>1.11.1009</version>

</dependency>

Please don’t forget that you need to change the base bucket search-insights-demo to the one you used when creating the database!

Testing time:

# Upload the parquet file to S3

curl -s -XPATCH http://localhost:8080/csv/s3/sample_data.parquet

The result should be the S3 URL where you can find the uploaded file.

Make Athena aware of newly uploaded data

AWS Athena does not constantly scan your base bucket for newly uploaded files. So if you’re attempting to DIY Site Search Analytics, you’ll need to execute an SQL statement that triggers the rebuild of the partitions. Let’s go ahead and add the necessary small changes to the FileService:

...

private static final String QUERY_REPAIR_TABLE = "MSCK REPAIR TABLE " + ANALYTICS.getName();

private final Path uploadLocation;

private final DSLContext context;

public FileService(ApplicationProperties properties, DSLContext context) {

this.uploadLocation = Paths.get(properties.getStorageConfiguration().getUploadDir());

this.context = context;

}

...

- First, we add a constant repair table SQL snippet that uses the table name provided by JOOQ’s code generation.

- Secondly, we autowire the DSLContext provided by Spring into our service.

- For the final step, we need to add the following lines to the public URL uploadToS3(String filename) method, right before the return statement:

...

context.execute(QUERY_REPAIR_TABLE);

That’s it! With these changes in place, we can test the final version of part 2

curl -s -XPATCH http://localhost:8080/csv/s3/sample_data.parquet

# This time, not only was the file uploaded, but the content should also be visible for our queries. So let's get the count of our database

curl -s localhost:8080/insights/coun`

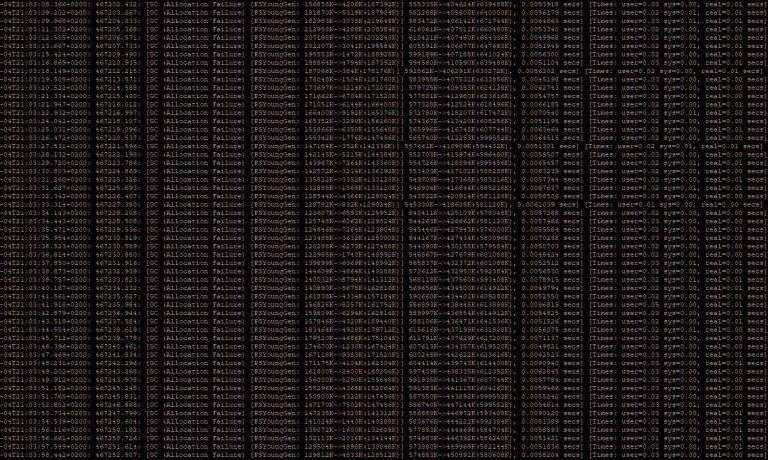

The response should match our expected value 3 — which matches the number of rows in our CSV file — and you should be able to see the following log message in your console:

Executing query : select count(*) from "ANALYTICS"

Fetched result : +-----+

: |count|

: +-----+

: | 3|

: +-----+

Fetched row(s) : 1

Summary

In part two of this series, we showed how to save storage costs and gain query performance by creating Apache Parquet files from plain old CSV files. Those files play nicely with AWS Athena, especially when you further partition them by date. E-Commerce KPIs can be partitioned precisely by a single day. After all, the most exciting queries span a range, e.g., show me the top queries of the last X days, weeks, months. This is the exact functionality we will add in the next part, where we extend our AthenaQueryServiceby some meaningful queries. Stay tuned and join us soon for part three of this series, coming soon!

By the way: The source code for part two can be found on GitHub.